CHAT WITH STIVEN LUKA – by Rafaela Prifti

Lidershipi i vetshpallur, pengmarresit e Vatres s’ka avokat qe i merr persiper.

Dokumentat zyrtare te Gjykates Federale tregojne qarte se avokati i tyre eshte terhequr, duke i lene pa perfaqesim dhe pa besueshmeri.

Menduan se me akuza te fabrikuara, presione dhe me gjyqe vatranet Agustin Mirakaj, Valentin Lumaj do terhiqeshin, por Gjykata Federale i hodhi poshte te gjitha pretendimet e tyre.

Menduan te benin edhe marrveshje duke shtyre sa here seancat ndonese ishin vet paditsit.

As kjo nuk u eci. Sot nuk kane me cfare t’u thone perkrahesve, sepse faktet flasin vete: rasti i tyre po shembet dhe avokati u dorezua para se te arrije ne salle te gjyqit.

Kryetarja e Miamit u ka thene hapur ne mbledhjen Zoom: nese humbisni gjygjin, jepni doreheqjen. Dega Jacksonville dhe Dega New Jersey e dine shume mire kush ka pas te drejte, dhe kjo eshte e qarte: Agustin M. Mirakaj ka pas te drejt. Dhe ai nuk ua ka borxh askujt, as Valentin Lumaj as Nazo Veliu, as Mark Mernacaj.

Vatran te nderuar, rrena i ka kembet e shkurtra. Dokumentat flasin. Koha e te vertetave po vjen.

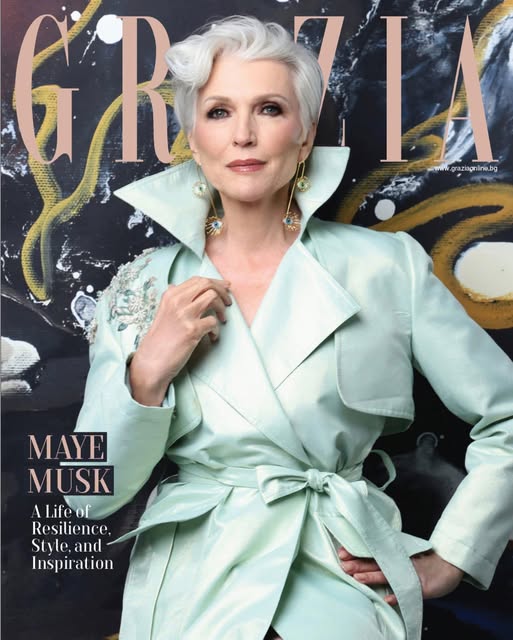

Vatra Manhattan Branch

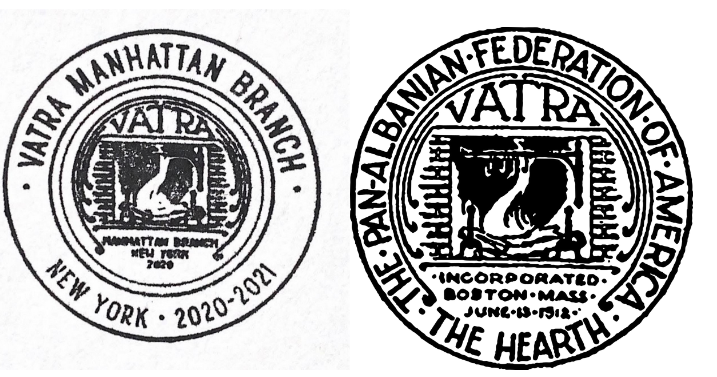

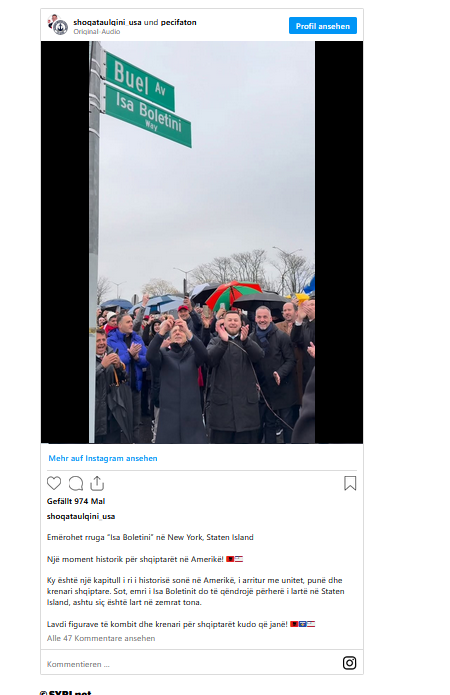

Të dielën, më 30 nëntor u përurua në New York emërtimi i një rruge me emrin e heroi, Isa Boletini.- Advertisement –

Kryetari i Mitrovicës, Faton Peci, i pranishëm në ceremoninë e inaugurimit, tha në një postim në Facebook se ky moment shënon jo vetëm respektin për një simbol të pathyeshëm të lirisë, por edhe lidhjen e fortë e të qëndrueshme mes popullit shqiptar dhe Shteteve të Bashkuara.

“Një moment historik për shqiptarët në Amerikë!

Ky është një kapitull i ri i historisë sonë në Amerikë, i arritur me unitet, punë dhe krenari shqiptare. Sot, emri i Isa Boletinit do të qëndrojë përherë i lartë në Staten Island, ashtu siç është lart në zemrat tona.

Lavdi figurave të kombit dhe krenari për shqiptarët kudo që janë!”, shkruhet në postim.

Z.Peci shkruan ne rrjetin social:

z.Naser Nika

Atëherë kur mendon se gjithshka po shkon në rregull dhe thua se; njoftimet janë bërë, qendra e zërit punon, njerëzit janë mbledhur dhe çdo pjesëmarrës është gati të ndjekë ceremoninë e Nderimit të Ditës së Flamurit të Shqipërisë në 113 vjetorin e Pavarësisë,… pikërisht atëhere moti në Uster përkeqësohet me stuhi ere dhe rreshje dëbore, por të pranishmit vazhdojnë për çka janë mbledhur, pa u tërhequr dhe nisin me himnet kombëtare të SHBA-ve dhe Shqipërisë.

Grupi i të Rinjve të Kishës Orthodokse Shqiptare Fjetja e “Shën Marisë”, zbulojnë me fjalimet e tyre në pak histori edhe qëllimin se përse ata janë mbledhur në sheshin para bashkisë së qytetit të duke treguar se janë pjesë e qytetarëve të tij dhe ruajtës e mbrojtës të traditave e vlerave të kulturës dhe familjeve shqiptare që janë thurur për më shumë se një shekull në jetën e shoqërisë amerikane.

Ashtu sikurse edhe një thënie e njohur për motin e bregut Veri Lindor të kontinentit të Amerikës së Veriut shpreh se “Nëse nuk ju pëlqen moti në New England, prisni një minutë”… kjo pikërisht sikur u plotësua në pasditen e 28 Nëntorit, 2025 kur një grup jo i vogël bashkatdhetarësh shqiptaro-amerikanë u mblodhën për të Nderuar Ditën e Flamurit, 113 vjetorin e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë.

Anthony Zdruli dhe Nick Prifti drejtuan mbarëvajtjen e këtij tubimi, duke u mbështetur nga të tjerë bashkëmoshatarë djem të rinj dhe vajza të reja, nga Grupi Valletona, nxënës shkollash, studentë kolegjesh të njohur apo që edhe sapo kanë dalë në jetë, si Ina Zhidro, Giulia Kosta, Ana Kodra të cilët ishin pjesë e fjalës poetike, e këngës dhe e valleve në këtë festë.

Kryetari i Bashkisë së Usterit Joseph M. Petty, drejtoi në fjalën e tij përshëndetjen për pjesëmarrësit, organizatorët, ish kryetaren Konstantina Lukes, këshilltaren Etel Haxhiaj, këshilltaren për arsimin Kathleen Roy dhe prefektin Niko Vangjeli dhe u ndal në dokumentin që zyra e tij njofton për Shpalljen e 28 Nëntorit, 2025 si Ditë e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë në qytetin e Userit duke inkurajuar banorët t’i bashkohen kësaj feste. Shqiptarët shpëtuan nga pushtimi 500 vjeçar otoman, Ismail Qemali ngriti Flamurin Në Vlorë dhe se “Dita e Flamurit” që nderohet çdo vit në Uster shpreh mirënjohjen se Usteri është shtëpia popullsisë shqiptaro-amerikan që ka shpërthyer me gjallërinë e saj dhe jep në shumë drejtime të jetës së qytetit, duke arritur sukses në fusha të ndryshme të përpjekjeve profesionale dhe interesit kulturor.

Vallja e Osman Takës, u hodh thuajse në kulmin e stuhisë, por të ftuarit ndoshta të mësuar me “tekat e motit”, shoqëruan valltarët, poezitë e recituara, muzikën dhe këngët e kënduara që përbënin në pjesë të rëndësishme të programit. Në mbyllje teksa pjesëmarrësit largoheshin duke marrë me vete mbresa dhe shpërndarë në rrjetet sociale atmosferën e festës, Anthony Zdruli si bashkë- organizator i veprimtarisë shpjegoi thjeshtë përvojën e një feste edhe ku stuhia e erës bie përpara një nisme të mirë që bëjnë njerëzit kur thotë:-“… kjo nuk na ndaloi. Ne prapë e festuam kjo është e rëndësishme dhe ju e dini që kjo ditë është Dita e Pavarësisë, që ka qënë e rëndësishme shumë vite më parë, mbi 100 vjet më parë. Dhe ndoshta i njëjti mot edhe atëherë. Kështu ne e dimë se çfarë të festojmë. Ndaj vazhdojmë dhe ja dalim me motin se dimë se si shkon” dhe në pak fjalë urimi i tij në gjuhën shqipe vjen i thjeshtë:-“Gëzuar ditën e Flamurit dhe Rrofsh Shqipëri”. Një urim të cilin të rinjtë e Usterit në Masaçusets e ndajmë me gjithë shqiptarët dhe arbëreshët kudo që ata ndodhen.

28 Nëntor, 2025

Uster, Masaçusets

Në metropolin e Çikagos, Komuniteti Shqiptar në Illinois – Albanian Community of Illinois me president të riun nga Presheva, Edon Shaqiri organizuan me shqiptarët Festën e Flamurit.

Në mesditën e 28 Nëntorit në DownTown, ndanë Rrugës Washington, u ngrit lart mes brohërimave Flamuri Shqiptar, aty mes rrokaqiejve, edhe mbi veprën monumentale dhe të njohur të Picasso-s, – shkruante shkrimtari Visar Zhiti. Në ceremoni ishin dhe kongresmeni Joe DioGurdi me bashkëshorten, po edhe Kosulli i Republikës së Kosovës, Drilon Zogaj .

Po kështu dhe në mbrëmjen festive në Niles. Salla e madhe ishte plot, e zbukuronin të rinjë dhe flamujt kudo, këngët dhe vallet.

Në fillim u kënduan dy Himnet Kombëtare, ai Shqiptar dhe ai Amerikan. Presidenti i Komunitetit, Edon Shaqiri, pasi do t’i uronte mirëseardhjen të githëve, do të fliste për rëndësinë e kësaj date dhe lavdinë e saj dhe do t’ia jepte fjalën “të Ftuarit të Nderit”, shkrimtarit Visar Zhiti.

Emocionuese do të ishin dhe kujtimet e çiftit Shirley dhe Joe Dio Guardi, puna e tyre e çmuar. Dhe do të shpërthente koncerti, këngët e njohura patriotike dhe valet gjithe larmi ngjyrash e flamuj. Një festë e madhe, e bukur, dinitoze dhe me estetik;e kombëtare. Njëri prej organizatorëve që shquhet, por për urtësinë, është trajneri nga Kërçova, Taip Bes Hiri, ideatori i takimit me kongresmenin, mik të hershëm që “nga lufta”. Gjithçka shkëlqen dhe ai rri në prapavijë, si të gjithë në festë…

Si një sintezë jo vetëm e asaj dite, por e ecurinë në shekuj të Flamurit Kombëtar po botojmë fjalën e shkrimtarit.

SHQIPONJË LIRI ME TË KUQEN DIELLORE…

Nga Visar Zhiti

Festën Kombëtare, më të madhen e shqiptarëve, atë të Flamurit, pra, të Pavarësisë, kur hidhen themelet e shtetit modern shqiptar, e festojmë me madhështi në Atdhe e në gjysmën tjetër të Atdheut, në Kosovë, kudo në Ballkan ku ka copëza Shqipërie e shqiptarë, përtej detit, në Itali me arbëreshët e këngës dhe të poezisë, në të gjithë Europën, edhe përkëtej oqeanit, në Amerikë, në mbarë botën dhe mbase më bukur në diasporë festohet në SHBA dhe po aq solelmnisht në Chicago.

Sot u ngrit Flamuri shqiptar në DownTawn, dhe u valëvit mes atij të SHBA dhe të Shtetit Illonois.

Kur u mblodhëm, pamë se ishim shqiptarë nga të gjitha trevat tona, vërtet Shqipëria natyrale, etnike, – vetëm në SHBA ndodh kjo, – dhe mes nesh erdhi me bashkëshorten e tij dhe kongresmeni i shquar, me origjinë arbëreshe, Joe DioGuardi, që i kushtoi jetën çështjes shqiptare, çlirimit të Kosovës.

Na bashkoi Flamuri ynë, më i bukuri në botë, besojmë ne.

Ky Flamur është ngritur hijerëndë në kështjella dhe pirgje dhe fusha beteje, ka mbulur heronjtë, por dhe nëpër dasma, vargani i krushqëve kishte kryeflamurtar, e mbajnë duart e fëmijëve, ky flamur ngrihet mbi institucionet shtetërore, presidencë, parlament, kryeministri, por dhe në ballkone pallatesh, ku banojmë, në tryeza pune e në zarfe me pullat postare, është në takime ndërkombëtare, ne ceremonira e në fusha sporti e festa e ngrihet lart bashkë me Himnin, ringrihet me çdo fitore e titull kampion, e gjejmë dhe në valixhe emigrantësh si amanet, në librat e shkollës dhe antologji poezish, në sheshe e në veprimtaritë kudo, në ambasada në të gjithë shtetet e në Organizatën e madhe të Kombeve të Bashkuara, aty me të gjithë flamujt e tjerë, i sigurtë, i barabartë.

SHEKUJT E FLAMURIT

Flamuri ynë ashtu si shqiponja e tij që shihej si një shpend hyjnor, vjen nga kohëra të lashta e mitologji, ka të bëjë me pellazgët, me të cilët janë të lidhur ilirët, siç besohet nga shumë shkencëtarë. Prandaj dhe na quajnë “Bij të Shqipes”!

Zjarr prometean Flamuri ynë, – kam thënë…

Shqiponja ishte emblemë dhe e Pirros së Epirit. Gjendet dhe te shteti i parë i Arbërit i viteve 1199-1216, që kulmoi me shtetin e Skënderbeut, ku Kastriotët e kishin dhe në stemën e tyre.

Gjergji ynë e ngriti mbi kalanë e Krujës, duke e çliruar nga pushtuesit otomanë në 28 Nëntor 1443, gati 6 shekuj më parë.

Me këtë Flamur Shqipëria u bë muri mbrojtës i Europës, i qyteterimit Perëndimor. Ai është Flamuri i “Atletit të Krishtit”, Skënderbeut, pa të cilin, – do të thoshte dhe në kongresin amerikan kongresmeni ynë, ndoshta dhe Amerika do të ishte ndryshe.

Dy kokat e shqiponjës janë Orienti dhe Oksidenti, duhet vëzhguar në dy kahet, bashkimi mban dhe universin. Kur u nda perandoria e Romës, gjysma që mbeti Bizant, e bëri symbol shqiponjën me dy krerë, e mbajtën ilirët, etj.

E kuqja e tij është kozmogoni, lidhet me dritën biblike, shpjegojnë studiuesit. Por do të simbolizonte dhe gjakun e derdhur për liri.

Donin ta copëtonin shpatat e perandorive dhe të ushtrive të huaja uzurpuese, gjylet e topave të tyre, donin ta grinin plumbat, ta zbehnin, ta përçudnonin duke i shtuar spatat liktoriane apo yllin e komunizmit, ai i sfidoi të gjitha dhe triumfoi.

Në shekujt e pushtimit Flamuri do të përndiqej, do ta mallkonin e do ta digjnin. Hiri i tij mbetej në kujtesën e Kombit.Dhe po harroj si ishte, ja ashtu si flakët…

Rilindasit rithirrën Skënderbeun. po Flamurin?

Që në vitin e parë të shekullit XX, një djalë 26 vjeçar, Faik Konica, në mërgim, në Bruksel, do të tregonte në gazetën “Albania”, që e themeloi vetë se “…flamuri ynë, i cili është një nga më të ndershmit dhe më të lavduarit të botës, është pa dyshim edhe një nga më të vjetrit”.

Me këtë Flamuar kishin shkuar dhe në Lidhjen e Dytë, atë të Prizrenit më 1887. Edhe arbëreshi Terenc Toçi e ngriti në Mirditë në vitin 1911.

Por një vit më vonë Plaku i bardhë, Ismail Qemali, pas 5 shekuj robërie, do ta ringrinte akoma më lart në Vlorë, po në 28 Nëntorin skënderbejan dhe shpalli pavarësinë e Shqipërisë dhe hodhi themelet e shtetit modern shqiptar. S’kishte institucione e as ngrehina për to, as hotele. Nëpër shtëpitë e vlonjatëve kishin bujtuar, ku kishte zjarr dhe zemër.Po rrinin bashkë përfaqësuesit e krahinave, ministrat që do të emëroheshin, asambleja, senati, luftëtarët, malsorët, qehallarë, rojet, etj, etj.

Ndërkaq nga Rumania erdhi Himni i Flamurit. U pëlqye dhe u këndua aq shumë sa nuk u zëvendësua dot me asgjë tjetër. Njëra nga strofat në kohën e komunizmit, jo vetëm që nuk këndohej, por do të hiqej dhe nga botimet:

Se Zoti vetë e tha me gojë

Se kombet shuhen përmbi dhé,

Por Shqipëria do të rrojë,

Për të, për të luftojmë ne.

Në 1913 Flamuri kombëtar është prapë në rrezik. Donin ta copëtonin Shqipërinë.At’ Gjergj Fishta ngre Flamurin mbi kambanoren e kishës së tij, si flatër engj;elli do ta quante dhe banderolat që nga aty do të lidheshin me minaret e xhamive.

MBËSHTEJA JETIKE E SHBA-së…

Roli i SHBA do të ishte vendimtar. Presidenti Wilson ndikoi shumë, I informuar dhe diaspora shqiptare, nga udhëheqësit e saj, Konica dhe Noli, kontakti me shqiptaro-amerikanët.Sot në Tiranë është një shesh që mban emrin e Presidentit shpëtimtar, Wilson, me shtatoren e tij në mes.

Lëvizje dhe rebelime dhe demonstra me Flamur bëheshin herë pas here dhe në Kosovën që vazhdonte të ishte e pushtuar deri vonë. Shpesh forcat policore gdhiheshin duke gjetur të ngritur qyteteve gjatë natës Flamurin shqiptar. Sikur mbinte vetvetiu.

Kur të burgosurit politikë u ngritën në Spaç në revoltën që tundi së brendshmi themelet e diktaturës, në 1973, ata ngritën në mes të kampit, brenda telave me gjëmba, Flamurin pa yllin komunist. Po ku e gjetën? Një këmishë të bardhë e ngjyen me gjakun e tyre dhe piktori i burgosur bëri shqiponjën. E ngritën lart duke kënduar himnin me lot në sy. Katër të burgosur i pushkatuan dhe ridënuan dhjetra të tjerë, por dhe vetë burgun.

Prapë në 28 Nëntor 1997 shpallet se është krijuar Ushtria Çirimtare e Kosovës.

Dhe po në 28 Nëntor në Kosovë kishte lindur legjenda Adem Jashari, në 1955 në Prekaz. Bënin dimra të acartë atëhere, por më keq se dimri ishte dhuna policore e regjimit serb ndaj shqiptarëve.

Në 28 Nëntor, ç’koinçidencë e bukur, që u tha dhe këtu, ka lindur dhe Presidenti Komunitetit Shqiptar në Illinois – Albanian Community of Illinois, Edon Shaqiri, familja e tij ikën nga Presheva nga shkaku I luftës n:e Shkup dhe prej andej në SHBA.

Dhe do të ndërhynin forcat e NATO-s dhe SHBA në këtë betejë, jo vetëm çlirimtare, por dhe morale, mbrohej një popull nga eksodi masiv si në Bibël. Pas bombardimeve të Beogradit, Kosova u shpall Republikë më vete. Shqipëria u fut në NATO dhe Flamuri i saj është bashkë me flamujt e forcave Perëndimore euroatlantike, me demokracitë më të përparuara.

Shqipëria dhe Kosova, dy shtete shqiptare të vegjël në Ballkan, por me histori të lashtë, kanë gjetur te Shtete Bashkuara të Amerikës së madhe aleatin jetik, mbrojtësin dhe mbështetësin.

Prandaj dhe sot Flamuri ynë si një vëllai vogël valëvitet pranë atij amerikan si një vëlla i madh, më i fuqishmi në botër dhe i drejtë.

Më bukur se gjithkund Flamuri ynë është në zemra, atje ku jemi bashkë, ja, si sonte…

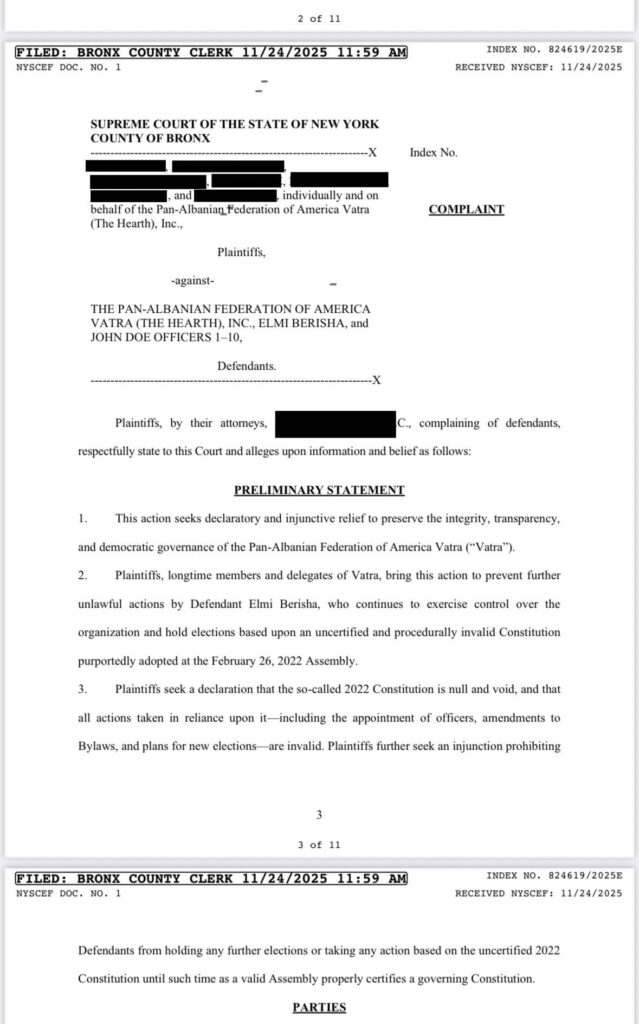

Vatrani i njohur Valentin Lumaj bënte me dije në rrjetin social si më poshtë:

“Nje grup zyrtaresh te Federates Vatra kane depozituar pardje nje padi ne Gjykaten Supreme te New York-ut kunder kryetarit te Vatres Elmi Berisha dhe ekipit te tij drejtues. Sikurse thuhet ne padi, ata kerkojne: : “masë ndaluese (kunder kryetarit Berisha), për të mbrojtur integritetin, transparencën dhe qeverisjen demokratike të Federatës Pan-Shqiptare të Amerikës, Vatra”.

Ata akuzojne lidershipin e Vatres si te pa-mandatuar dhe pa baze ligjore per te drejtuar organizaten.

Eshte interesante se, qysh nga zgedhja e tij, kryetari i Vatres eshte kontestuar ne vazhdimesi nga anetaresia e Vatres dhe qe nga viti 2021, pra me pak se 5 vite, Vatra numeron 8 procese gjyqesore, padi e kunderpadi, keto ne gjykatat me te larta, si ne Gjykaten Federale dhe Gykarten Supreme etj. Pra i bie qe shumicen e kohes e tij si kryetar i Vatres, ai e ka kaluar ne gjyqe me vatrane. Ne fakt e gjithe kjo kohe, finance dhe energji vatrane, mendoj se duhej shpenzuar ne Washington per Shqiperine dhe Kosoven.

Dikur Vatra gjyqet i kishte me greker e serbe, tani po “i nxjerrim syte” njeri-tjetrit. Sa keq ku kemi mberritur!

Urime dhe suksese grupit te vatraneve! Dhashte Zoti paqe ne Vater dhe Vatra te kthehet ne binare kushtetues dhe ne misionin e saj perbashkues dhe mbrojtes te interesave shqiptare ne USA.”, përfundon Valentin Lumaj.

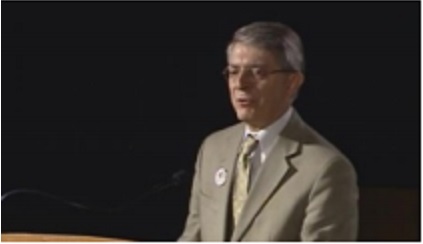

Në njëvjetorin e ndarjes nga jeta të Profesor Sami Repishtit

Sot, më 27 nëntor, përkujtojmë me mall dhe nderim njëvjetorin e ndarjes nga jeta të Prof. Sami Repishtit, një figure që nuk i përket vetëm kujtesës sonë intelektuale e patriotike, por edhe ndërgjegjes kombëtare shqiptare.

Humbja e tij la një boshllëk të thellë që vetëm njerëzit e mëdhenj dinë ta lënë pas vetes.

Ai nuk ishte vetëm akademik i shquar, intelektual, letrar e humanist i rrallë, por mbi të gjitha atdhetar i palodhur, zë i ndërgjegjes shqiptare dhe udhërrëfyes moral për brezat.

Ishte luftëtari më dinjitoz i lirisë së Kosovës. Përmes fjalës, veprës dhe shembullit të tij, ai mishëroi ndershmërinë, guximin dhe dashurinë për lirinë.

Lindur në Shkodër, qytetin që ka dhënë shumë figura të ndritura të kombit, pinjoll i një familjeje fisnike, Prof. Repishti u rrit me bindjen se liria nuk është dhuratë, por detyrë.

Qysh i ri, ai sfidoi padrejtësinë dhe diktaturën komuniste, dhe për këtë pagoi çmimin më të lartë: dhjetë vjet burg, përndjekje dhe vuajtje të papërshkrueshme.

Por as errësira më e thellë e burgjeve nuk mundi ta shuante zjarrin liridashës në shpirtin e tij.

Në vitin 1959, ai u largua nga Shqipëria, jo për t’i shpëtuar veten por për të ruajtur idealet dhe për ta mbajtur gjallë shpresën për Atdheun e lirë.

Në Shtetet e Bashkuara të Amerikës, ku e priti jeta e re, ai u bë profesor i respektuar, krijoi një familje të ndershme e të dashur, bēri miq dhe admirues në rrethe akademike e shoqërore, duke u integruar plotësisht në jetën amerikane që u bë atdheu i tij i dytë.

Por zemra dhe shpirti i tij mbetën përherë shqiptare.

Ai ishte krijuesi dhe mendimtari, disidenti dhe ish-i burgosuri politik, intelektuali dhe humanisti i pakrahasueshëm.

Një ikonë antikomuniste dhe qëndrestar i përbetuar, që nuk hoqi dorë kurrë nga kauza e çlirimit të Kosovës.

Rilindësi i fundit, “kosovari i Shkodrës” si quenin,Prof. Sami Repishti, ishte dhe mbetet shërbëtori më i përkushtuar dhe më besnik i çështjes së Kosovës.

Në çdo fjalë dhe shkrim, ai foli për lirinë e shqiptarëve nën diktaturë, për dinjitetin njerëzor dhe për bashkimin kombëtar.

Edhe pse i përndjekur nga regjimi komunist, pas vendosjes në SHBA, ai e bëri kauzën e Kosovës qëllimin e jetës së tij publike.

Ai besonte se çlirimi i Kosovës ishte themeli moral i ribashkimit shpirtëror të kombit.

Në një nga thëniet e tij të përsëritura, Prof. Repishti shprehej:

“Komunizmi do të bjerë herët a vonë. Shqipëria do të mbetet përsëri shtet i pavarur.

Por Kosova është plaga që kullon gjak e që kërkon liri dhe vetëvendosje.”

Në çdo ligjërim, letër apo bisedë, ai përsëriste fjalë që sot tingëllojnë si amanet:

“Nuk ka gjë më të shenjtë se jeta e njeriut dhe dinjiteti i tij.”

“Dija është pasuria më e madhe e një kombi. Ta ndajmë, ta përhapim dhe ta përdorim për të mirën e njerëzve tanë.”

“Kur ideologjia bëhet më e rëndësishme se bashkimi për kombin, atëherë kemi arsye për frikë.”

“Zëri i atyre që nuk kanë zë është zëri që duhet dëgjuar më së pari.”

Unë pata fatin të njihem me Prof. Repishtin para pesëdhjetë vitesh. Që atëherë mbetëm miq përjetë.

Ai më afroi si mik, mentor dhe bashkëpunëtor në kauzën e shenjtë për lirinë e Kosovës.

Nuk ishte thjesht figurë publike, por njeri me zemër të madhe, mendje të kthjellët dhe shpirt të pathyeshëm.

Dinte të dëgjonte, të qeshte, të argumentonte me intelekt të hollë dhe qartësi shpirtërore.

Modestia e tij ishte virtyt për t’u admiruar. Ai nuk kërkoi kurrë lavdi për veten, as mburrje, edhe pse kishte fituar mirënjohje dhe dekorata të shumta nga institucione e personalitete të njohura në SHBA dhe në Evropë.

Gjithçka që bëri, e bëri për kombin, për Kosovën, për të ardhmen.

Ishte ndërgjegje, frymëzim dhe motivues.

Kur u nda nga kjo botë, më 27 nëntor 2024, ai mori me vete paqen që e meritonte, por la pas një trashëgimi që do të jetojë përtej brezave, në libra, kujtime dhe në zemrat e atyre që patën fatin ta njohin.

Shkoi për t’u bashkuar me gegët e mëdhenj shkodranë, bashkëvuajtës të idealit; Arshi Pipën e Martin Camajn, si dhe me shumë e shumë atdhetarë të ardhur nga Kosova dhe viset tjera shqiptare të Ballkanit të egër.

Sot, në këtë përvjetor kujtese, ne nuk përkujtojmë vetëm intelektualin, krijuesin, disidentin dhe atdhetarin, por simbolin më dinjitoz e artikuluesin më të denjë të vlerave të diasporës shqiptare në Amerikë , zëdhënësin dhe shembëlltyrën që na mësoi se dinjiteti njerëzor dhe e vërteta janë themelet e lirisë.

I nderuari Profesor Sami Repishti, edhe pse fizikisht jemi të ndarë, shpirtërisht mbetemi bashkë me ty në kujtimet, mësimet, dashurinë dhe respektin që ke lënë pas.

Pusho në paqe, shpirti fisnik, mendimtari, atdhetari dhe humanisti i përkushtuar,

miku im, Profesor Sami Repishti

Një libër i ri nga Fron Nahzi hulumton dokumentet amerikane për të parë se si komuniteti i shqiptarëve në SHBA punoi për të siguruar mbështetjen amerikane për atdheun e tyre.

Libri i ri i Fron Nahzit, Pushtet, identitet dhe politikë: një vështrim kritik mbi Lëvizjen Shqiptaro-Amerikane ofron diçka të rrallë: një studim mbi lobimin e një grupi etnik; studimi është teorik pa u bërë i thatë, historik pa u bërë bajat dhe personal deri në një farë mase, pa rënë në botën e kujtimeve apo përgëzimeve të vetvetes.

Historia shqiptaro-amerikane është diçka në të cilën Nahzi ka jetuar vetë, e ka studiuar dhe analizuar për dekada dhe shumë pak njerëz janë në pozicion më të mirë se ai për të treguar këtë histori, një histori të cilën ai e paraqet me njohuri të thella, anektoda dhe herë pas here, me shaka të këndshme.

Rezultati i të gjithë kësaj është studimi më serioz dhe tërësor deri më sot mbi bashkësinë e shqiptarëve të amerikës: se si anëtarët e saj arritën atje, si u organizuan dhe si u përpoqën të ndikojnë politikën e SHBA-ve drejt Shqipërisë, Kosovës dhe më gjerë ndaj rajonit të Ballkanit. Siç shkruan Nahzi: Shtetet e Bashkuara i dhanë këtyre emigrantëve diçka që atdheu nuk mundej t’ua siguronte. “Lirinë për të advokuar për kauzën e tyre nacionaliste… pa frikën se do të përndiqeshin nga shteti”:

Gjithsesi glorifikimi nuk është qëllimi i librit. Bashkësisë nuk i mungojnë njerëzit që pretendojnë se kanë ndryshuar politikën e Uashtingtonit në çaste kritike, duke përmbysur diktatorë dhe duke mobilizuar forcat e NATO-s. Nahzi i kundërvihet këtyre miteve duke shpjeguar realitetit politike dhe interesat amerikane në kohën përkatëse, duke u mbështetur te kërkimi në arkiva, intervista dhe vëzhgime personale – ndërkohë që vlerëson aktivizmin këmbëngulës që me të vërtetë pati rëndësi.

Për të shpjeguar historinë e këtij komuniteti, ai përqendrohet në tri kauza madhore politike që frymëzuan aktivizmin e shqiptaro-amerikanëve që nga mesi i shekullit të 19, kur emigrantët relativisht të varfër dhe të paarsimuar hasën bashkësitë më të vjetra dhe me rrënjë më të forta të italianëve, serbëve e grekëve.

Kauza e parë i përket fillimit të viteve 1900 dhe konsistonte në nxitjet për një Shqipëri të pavarur dhe të bashkuar pas Luftës së Parë Botërore. Kjo kauzë u përball me vështirësi të mëdha. Një memo e vitit 1919 për presidentin Ëoodroë Ëilson hidhte poshtë idenë e një Shqipërie të pavarur si një “entitet politik që me shumë gjasa do të jetë i padëshirueshëm”. Pjesë të mëdha të tokave të banuara nga shqiptarët iu dhanë Greqisë, Serbisë dhe Malit të Zi. Njohja e Shqipërisë nga SHBA erdhi vetëm më 1922 dhe vetëm pasi në det u zbulua naftë.

Kauza e dytë madhore u shfaq gjatë Luftës së Ftohtë me lëvizjen anti-komuniste. Nga viti 1949 deri në vitin 1956, SHBA dhe Britania ndërmorrën operacione sekrete duke përdorur të arratisurit nga Shqipëria – përpjekje që dështuan për shkak të planifikimit të keq, kontrollit të rreptë të vendit nga regjimi komunist dhe tradhëtisë së agjentit të dyfishtë britanik Kim Philby. Më shumë se 200 shqiptarë që u hodhën me parashutë në Shqipëri u kapën ose u vranë.

Qeveria amerikane më vonë krijoi Komitetin për Shqipërinë e Lirë, pjesë e një fushate më të gjerë për të luftuar komunizmin nëpër të gjithë bllokun sovjetik. Anëtarë të bashkësisë shqiparo-amerikane, shumë prej të cilëve ishin nga veriu i Shqipërisë dhe antikomunistë të fortë, luajtën rol kyç në këtë, duke kontrolluar më shumë se 10 mijë familje për emigrim në SHBA, përfshirë familjen e Nahzit.

Mbështetja për Berishën

Ndërsa glasnosti dhe perestrojka fituan terren dhe diktatura shqiptare u lëkund, diaspora u bë edhe një herë e rëndësishme në Uashington, duke ofruar të dhëna për një vend që kishte qenë i mbyllur hermetikisht që prej dekadash. Kur marrëdhëniet diplomatike u rivendosën më 1990, Departamenti i Shtetit nuk dispononte një flamur shqiptar për ceremoninë.

Diaspora mbështeti Sali Berishë, udhëheqësin karizmatik të Partisë Demokratike, një parti e sapokrijuar, ndërsa Berisha u bë president i vendit. Zelli i tij anti-komunist dhe rrënjët e tij nga veriu i kishte të përbashkëta me shumë anëtarë të diasporës. Këto vunë në hije shërbimin e tij të gjatë në sistemin komunist si dhe prirjet autoritariste që shfaqi shpejt pasi mori pushtetin.

Siç vëren Nahzi, mbështetja që bashkësia shqiptaro-amerikane i dha Berishës, pavarësisht tendencave të tij jodemokratike, ishin pjesë e një tendence më të gjerë. Shqiptaro-amerikanët shpesh thirrën në ndihmë arsyet morale dhe të drejtat e njeriut për të argumentuar në mbështetje të ndërhyjes amerikane; (ata citonin doktrinën e Ëilson për vetëvendosje të kombeve për Pavarësinë e Shqipërisë apo vinin në duke krimet e luftës në Kosovë); megjithatë, ata shpesh dështuan të mbajnë përgjegjës udhëheqësit e vendit të tyre për këto standarde.

Kauza e tyre e madhe finale ishte Kosova. Diaspora u mobilizua duke ndërgjegjësuar faktorët politikë mbi represionin e viteve 1980 dhe krimet e viteve 1990, duke ndihmuar për të ngritur momentumin politik për ndërhyrjen e NATO-s në vitin 1999. Ndërsa Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës u rrit në famë, shqiptaro-amerikanët intensifikuan përpjekjet për grumbullimin e ndihmave përmes fushatës “Atdheu thërret” ndërsa disa qindra të rinj u bashkuan me “Brigadën e Atlantikut” për të luftuar.

Përgjatë këtyre epokave, vëren Nahzi, diaspora u shfaq më e fortë në kohë krizash, të cilat gjeneruan një qëllim të përbashkët – formimin e shtetit, anti-komunizmin dhe luftën. Këto sfida fuqizuan solidaritetin që mbushi ndasitë brenda komunitetit, të tilla si krahina, feja apo bindjet politike.

Ky bashkim në përgjithësi sot nuk ekziston. Në lidhje me Kosovën, ku problemi i statusit vijon të mbetet i pazgjidhur, vëmendja e bashkësisë shqiptaro-amerikane është pakësuar ose është ndarë në axhenda konkurrente. Në Shqipëri, angazhimi gjithnjë e më shumë ushqehet nga interesat financiare. Në të dyja vendet, udhëheqësit politikë synojnë të lidhen me shqiptarë të pasur në SHBA më shumë se sa më gjerë me komunitetin. Shumë grupe lobimi apo advokimi kanë pakësuar aktivitetin ose kanë kaluar në gjendje të fjetur dhe nuk ka shumë ndjesi për prioritetet e atdheut.

Ajo që mungon, vëren Nahzi, është angazhimi afatgjatë për demokracinë dhe problemet që shkojnë përtej vijave ndarëse: arsim, shtet të së drejtës, ndërtimit të institucioneve dhe luftës kundër korrupsionit. Diaspora shqiptare mbështeti fort kauzat e rëndësishme të pavarësisë dhe rezistencës por ka investuar më pak, thotë ai, në vlerat dhe strukturat e nevojshme për të siguruar qeverisje demokratike, mirëqenie dhe stabilitet afatgjatë.

Marrë nga BIRN

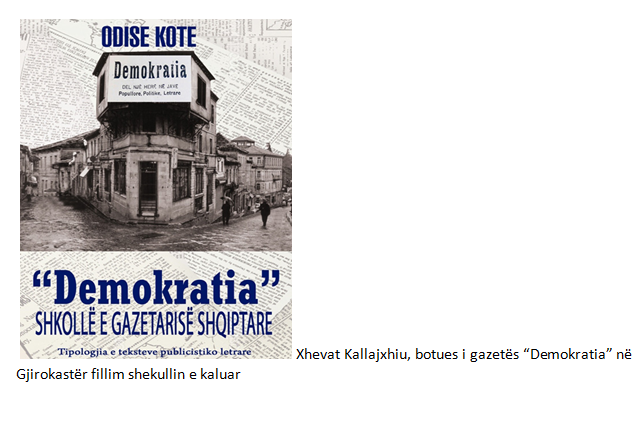

NË KUJTIM TË XHEVAT KALLAJXHIUT NJËRIT PREJ DEKANËVE TË GAZETARISË SHQIPTARE

Nga FRANK SHKRELI

Xhevat Kallajxhi – gazetari dhe autori shqiptaro-amerikan ndërroi jetë nëntorin e vitit 1989, në prag të ndryshimeve rrënjësore historike me shembjen e komunizmit ndërkombëtar anë e mbanë Europës Lindore e Qëndrore dhe në Shqipërinë e tij të dashur. Ai u largua nga kjo jetë 25 vjetë më parë qetësisht, ashtu si edhe jetoi jetën — të pakën jetën gjatë të cilës e njoha unë. Megjithëse i pëlqente debati dhe kishte një njohuri të gjërë mbi subjekte të ndryshme, ashtu siç ndodhë me gazetarët e mirë, Xhevati nuk turbullonte as nuk grindej me askënd, madje as me ata që nga ndonjëherë e kritikonin me pa të drejtë, përfshirë këtu edhe bashkqytetarin e tij gjirokastrit, diktatorin Enver Hoxha i cili në disa raste në kujtimet e tija kishte kritikuar Xhevatin si “njërin që pretendonte të ishte gazetar”. Xhevat Kallajxhiu vdiq më 8 nëntor, 1989, në moshën 85-vjeçare, në një lagje të shtetit Maryland, afër Washingtonit, kryeqytetit të Shteteve të Bashkuara ku kishte punuar për shumë vite pranë seksionit shqip të Zërit të Amerikës. Ndonëse komuniteti shqiptar në Washington ishte tepër i vogël në atë kohë, Xhevati u përcoll në atë jetë vetëm nga familja e tij e ngushtë dhe nga një grusht bashkatdhetarësh nga Gjirokastra ku kishte lindur dhe nga zona të tjera të Shqipërisë, përfshirë edhe disa të ardhur rishtas në Amerikë — refugjatë politikë të arratisurish nga trojet shqiptare nën ish-Jugosllavi. Të pranishëm për t’i dhënë lamtumirën e fundit Xhevatit ishin edhe miqë amerikanë të familjes Kallajxhiu.

Xhevat Kallajxhiu kishte punuar për shumë vite pranë seksionit shqip të Zërit të Amerikës, aty ku e kisha takuar për herë të parë në qershor të vitit 1974, kur unë fillova punën së pari në të njëjtën zyrë. Gjatë disa viteve që punova me të, Xhevat Kallajxhiu, për mua ai ishte një shkollë gazetarie. Për më tepër, ai ishte ndër shqiptarët e pakët që kisha takuar e që besonte me mish e me shpirt në të drejtat e njeriut për çdo qënje njerzore, për lirinë dhe demokracinë për çdo popull, por mbi të gjithë, për kombin shqiptar. Ai ishte plot frymëzim për një ditë më të mirë për kombin shqiptar dhe për njerëzimin, ndonëse kishte edhe momente kur ankohej për vuajtjet e shqiptarëve kudo.

Si redaktor përgjegjës i gazetës Dielli, Xhevati si asnjë herë më parë, shumë shkrime të tija ia kishte kushtuar Kosovës dhe gjendjes së shqiptarve nën ish-Jugosllavi dhe gjithashtu i hapi faqet e gazetës edhe e për të tjerët për të rrahur çështjen e Kosovës dhe të të drejtave të njeriut për shqiptarët në trojet e veta. Interesimin dhe dashurinë e tij për Shqipërinë dhe shqiptarët, ai e pasqyroi me vepra dhe me fjalë gjithë jetën e tij, ashtu siç demonstroi edhe dashurinë e tij njëkohësisht edhe për Amerikën, ndërkohë që promovonte me gjithë potencialin e tij miqësinë midis Kombit shqiptar dhe Shteteve të Bashkuara të Amerikës. Ai ishte një gazetar dhe autor i denjë, i cili me ushtrimin e gazetarisë, ai jepte nder kësaj fushe, sidomos gazetarisë shqiptare. Në krijimtarinë e tij krijuese, si në gazetari, ashtu edhe në prozë dhe deri diku edhe në poezi, megjithëse thonte se nuk ishte poet ndërkohë që i kërkonte lexuesit që të “gjykonte vjershat e tij nën prizmën e ndjenjës” Xhevati mbeti gjithmonë i lidhur me dhe pranë lexuesit shqiptar. Si i tillë, gjatë shërbimit të tij në Zërin e Amerikës ose me shkrimet e tija të shumëta me pseudonimet “Bardhi” dhe “Gjin Shpata” në gazetën Shqiptari i Lirë dhe në gazeta e revista të tjera, por sidomos në periudhën që ai ishte Kryeredaktor i organit të Organizatës panshqiptare Vatra, gazetës Dielli — Xhevati e tregoi se ishte jo vetëm pjesë e pa ndarë e Gjirokastrës dhe Shqipërisë që e lindi por edhe i të gjitha trojeve shqiptare në Ballkan. Si shumë patriotë të gjeneratës së tij, Xhevat Kallajxhiu i ndiqte për së afërmi vujajtjet e shqiptarëve të Kosovës dhe shkruante shpesh për fatin e tyre. Ishte me të vërtetë i përkushtuar ndaj fatit të Kosovës. Shumë artikuj dhe kryeartikuj kanë dalë nga dora e tij, numri të cilëve ndoshta nuk do të dihet kurrë, mbi shumë subjekte, përfshirë Kosovën. Në një kryeratikull në gjuhën anglisht, me rastin e 5-vjetorit të demonstratave të vitit 1981 në Kosovë, Xhevati shkruante, se “Ndërsa kujtojmë 5-vjetorin e demonstratave në Kosovë, ne jemi të bindur se shqiptarët anë mbanë botës do të kujtojnë me respekt të thellë të gjithë ata që dhanë jetën në demonstratat si edhe ata që tani po vuajnë në burgjet e Jugosllavisë për pjesëmarrjen e tyre në demonstrata. Të gjithë ata janë heronjë të një kauze të drejtë, kauzë e cila heret ose vonë, do të triumfojë”, përfundonte kryeratikullin largpamës Xhevat Kallajxhiu të shkruar më 1986.

Gjatë periudhës që ai punoi tek Zëri i Amerikës, Xhevati me kolegët e tij — në radhët e të cilëve ai gëzonte një respekt jashtzakonisht të madh si koleg dhe si profesionist — gjatë luftës së ftohtë shërbeu si shembull i lirisë së shtypit dhe të debatit të lirë dhe megjithë rrethanat e vështira ata u përpoqën t’i jepnin dëgjuesve shqiptarë kudo — nepërmjet radios me valë të shkurtëra — një alternativë ndaj një shtypi që dominohej dhe kontrollohej plotësisht nga regjimi komunist në Shqipëri dhe në trojet e tjera shqiptare. Kurrë nuk lodhej dhe nuk ankohej asnjëherë për punën e rëndë si rrjedhim i mungesës së stafit të kualifikuar. I vetmi shqetësim i Xhevatit ishte se mos po e bënim gjithë atë punë kot sepse nuk kishim asnjë të dhënë nëse na ndëgjonte njeri. Shpeshherë duke u këthyer nga studio, Xhevati këthehej e më pyeste: “E mo Frank, e bemë gjithë këtë punë, thua na dëgjoj njeri sot?” Fatkeqsisht, ai si shumë të tjerë të brezit të tij, nuk pati fatin të ishte dëshmitar i fruteve të punës së tij prej dekadash për lirinë e popullit të vet dhe të përjetonte më në fund shëmbjen e komunizmit në Shqipërinë e tij të dashur dhe lirinë e pavarësinë e Kosovës. Në shkrimet e tija, ai i kishte kushtuar një hapësirë të madhe kërkesave legjitime të shqiptarëve të Kosovës për liri e pavarësi. Por Xhevati mund të mbetet i kënaqur në atë jetë, se puna dhe mundi i tij tek Zëri i Amerikës nuk i kishte shkuar më kot. Po të ishte gjallë, ai do të mësonte ashtu siç mësuam të gjithë pas rënjes së regjimit komunist, se Zëri i tij dëgjohej — ndonëse fshehurazi — dhe se për një kohë të gjatë përbënte të vetmen alternativë ndaj shtypit të kontrolluar nga regjimi komunist i Enver Hoxhës.

Veprimtaria gazetareske e Xhevatit kishte filluar në rini në qytetin vendlindjes së tij në Gjirokastër. Fillimisht, më kujtohet të ketë përmendur bashkpunimin e tij me gazetën Labërija, por nuk më kujtohet se në çfarë kapaciteti dhe për sa kohë ka punuar pranë kësaj gazete. Por, ai fliste me krenari për punën e tij pranë gazetës “Demokratia”, e cila u botua nga viti 1925 deri më 1939 në Gjirokastër. Përveç gazetarisë serioze, Xhevati merrej edhe me humor të cilin ai e kishte shprehur në revistën “Pif-Paf” në Shqipërinë e para luftës, por nga humori nuk hoqi dorë as në Amerikë, ku kishte botuar librezën humoristike “Për të Qeshur”.

Pasi u largua nga Zëri i Amerikës, Xhevat Kallajxhiu shërbeu si kryeredaktor i gazetës Dielli për 10-vjetë gjatë 1970-ave dhe 1980-ave, nën rrethana shumë të vështira për ‘të personalisht sepse jetonte afër Washingtonit, ndërkohë që kryeqendra e organizatës Vatra dhe e gazetës Dielli ishte në Boston. Por, ky ishte përkushtimi moral dhe patriotik i Xhevatit, ndonëse në rrethana mjaft të vështira materiale dhe financiare për gazetën Dielli, në një kohë që ekzistonte rreziku të shuhej gazeta, Xhevat Kallajxhi ndonëse në mosh të shkuar, i del zot Diellit, i cili në kohërat më të vështira për Shqipërinë dhe për shqiptarët lëshoi rreze drite me shkrimet dhe artikujt e peshkop Fan Nolit, diplomatit Faik Konicës dhe shumë shkrimtarëve dhe gazetarve të tjerë shqiptaro-amerikanë, ndoshta më pak të njohur se këta, por me mundësitë e veta edhe ata kontribues ndaj kulturës dhe gazetarisë shqiptare në mërgim dhe më gjërë — të cilët Xhevati i inkurajonte të shkruanin dhe të bashkpunonin me gazetën Dielli.

Me rastin e 25-vjetorit të vdekjes, Kryeredaktori i tanishëm i gazetës Dielli, Dalip Greca, si pasardhës i denjë i Xhevat Kallajxhiut dhe të tjerëve që kanë udhëhequr Diellin për më shumë se një shekull, iu përgjij kërkesës time që të vlerësonte punën e Xhevatit si kryeredaktor i gazetës Dielli, si dhe përfshirjen e subjekteve që trajtonte Xhevati gjatë një dekade me shumë rëndësi për fatin e shqiptarëve: “Xhevat Kallajxhiu mbetet një ikonë e rrallë në gazetarinë e mërgimit”, tha Z. Greca. “Kontributi i tij prej një dekade në gazetën Dielli, është me vlera jo vetëm për kohën kur shkroi dhe editoi Diellin, por edhe për brezat në vazhdim. Ishte njohës i mirë i historisë botërore, vecanërisht asaj amerikane dhe shqiptare, çka pasqyrohen në artikujt e tij historikë. Ai e orientoi Diellin drejt shqetësimeve reale të komunitetit, të Vatrës, dhe Çështjes Shqiptare në tërësi”. Dalip Greca, si njohës i mirë i shkrimeve të Xhevatit për gazetën Dielli, shtoi se Kallajxhiu, “I dha hapësirë mbrojtjes të të drejtave të shqiptarëve në ish Jugosllavi e në Shqipëri, denoncoi shkeljen e të drejtave njerëzore, shtroi me guxim probleme para komunitetit, evokoi historinë Kombëtare, evidentoi vlerat e Vatrës dhe të Diellit, shkroi e përcolli me shpirt e sy të përlotur bashkadhetarët që ndërruan jetë. Xhevati ka lënë pas gjurmët e një njeriu me shpirt njerëzor, të dashur, të respektuar. Flet pena e tij në rreshtat e Diellit”, shtoi Dalipi.

Si njohës i mirë i kontributit dhe shkrimeve të Xhevat Kallajxhiut për gazetën Dielli, ku ruhet koleksioni i shumë shkrimeve të tija, Z. Greca e vlerëson kështu rolin e Xhevatit si kryeredaktor i Diellit për një dekadë: “Ai ishte gazetari që të imponon edhe sot t’ia lexosh artikullin. Ishte mjeshtër për të thënë shumë gjëra në pak radhë. Nuk kërkonte fjalë bombastike; jo, fjalori i tij rridhte natyrshëm dhe kishte parasysh lexuesin e Diellit. I përshtatej. Stili i tij është i vecantë. Them se e kishte krijuar stilin e vet. Përherë nisej nga faktet për të shtruar idetë. Mendoj se editorialet e tij mund dhe duhet të studiohen nga shkollat e gazetarisë në Tiranë, Prishtinë, Tetovë e Shkup. Xhevati tregonte kujdes që në përcaktimin e titullit, të shkrimit; edhe sot kur i shfletoj koleksionet e Diellit, harrohem me orë të tëra sepse më fusin në kurth titujt. Pasi shoh titullin provoj një thirrje të brendshme që ta filloj dhe s’mund të heq dorë pa i shkuar në fund. Ka qenë shumë prodhimtar. Nuk ka numër të Diellit për 10 vitet që e editoi Xhevati, që të mos gjesh editorialet e tij me emër. Po përmend disa nga titujt e editorialeve të Xhevatit: “U mbars Mali dhe polli një mi”; Hakmarrja-Një zakon i keq; Të njohim njëri-tjetrin; Fati i të burgosurve të Kosovës, Gjallëria e racës shqiptare, “Arratisen nga “parajsa e Kuqe”, Mirënjohje shqiptare për Amerikën”, e tjera .

Është e vërtetë se bazuar jo vetëm në shkrimet e tija gjatë një dekade që ai drejtoi Diellin, por edhe në biseda private e shoqërore — megjithëse ishte kulmi i luftës së ftohët dhe komunizmi dukej më i fortë se kurrë — Xhevati shihte tek e ardhmja me optimizëm për kombin shqiptar. Në kryeartikujt e tij, Xhevati shtroi problemin e bashkimit Kombëtar, si ndreqje e padrejtësive të Europës, që e kishte coptuar Kombin shqiptar, tha kryeredaktori i Diellit.

Përveç kontributit të tij prej dekadash në fushën e gazetarisë me qindra artikujsh e kryeartikujsh të nënshkruar prej tij jo vetëm me emërin e tij të saktë por edhe me pseudonimet “Bardhi” dhe “Gjin Shpata” — si njëri prej dekanëve të gazetarisë shqiptare — Xhevat Kallajxhi është edhe autor i një numri librash e librezash botuar këtu në Shtetet e Bashkuara, me prozë dhe poezi. Ndër ato që dallohen janë libri me poezi, “Tingëllimet e Zemrës”, dhe Lot e Shpresa, të cilin ai ua ka “kushtuar me nderim shokëvet që kanë vdekur në mergim”. Disa nga vjershat, Xhevati ia ka kushtuar Kosovës siç janë poezitë “Kosova Martire”, “Kosova” dhe “Marshi i Djelmënisë Kosovare”. Xhevati i këndon gjithashtu “Çamerisë”, “Arbëreshve të Italisë”, “Statujës së Lirisë” dhe vjershën kushtuar, “Dom Ndre Zadesë”, patriotit të flakët, klerikut dhe shkrimtarit, siç e quan atë Xhevati, i cili ishte nga viktimat e para që u pushkatua nga komunistët, pranverën e vitit 1945 në Shkodër.

Duke qenë me mundësi të kufizuara financiare, vjershat patriotike kushtuar dëshmorëve dhe si edhe punimet e tjera të Xhevatit janë botuar me ndihmën bujare të bashkatdhetarve të tij në Amerikë. Kjo bëri të mundur që Xhevati të botonte disa libra shqip në Shtetet e Bashkuara, përfshirë Linkolni, Xhon F Kennedy, Për të Qeshur, Bektashizmi dhe Teqeja Shqiptare në Amerikë. Thuhet se Xhevati mund të ketë lënë edhe disa dorëshkrime pa botuar, siç është edhe romani Larg Atdheut.

Xhevati njihej, bashkpunonte dhe vlerësohej pa dallim nga mbarë elita politike dhe kulturore e komunitetit shqiptaro-amerikan. Si rrallë të tjerë bashkohas të tij të cilët shpesh tregonin paragjykime mbi arsyen — atë nuk e pengonin ndryshimet politike, krahinore ose fetare në punën e tij drejtë realizimit të qëllimeve të përbashkëta. Një bashkohas i tij, ish-profesori i njohur shqiptaro-amerikan, i ndjeri Peter Prifti ka vlerësuar se Xhevat Kalljaxhiun si gazetar, si njeri dhe si patriot duke thënë se Xhevat kallajxhiu, “Në tërësi shkruante duke pasur gjithmonë respekt për faktet dhe duke patur përmbajtje prej dijetari. Nga temperamenti ishte idealist me simpati të thella humanitare për të shtypurit. Në jetën e tij pati mjaft dhimbje e vuajtje, por fatkeqësitë i mbarti me shpirt të qetë dhe me sens humori.” Duke vlerësuar Xhevat Kallajxhiun jo vetëm si njeri dhe si gazetar por edhe si patriot, si demokrat dhe si besimtar i fortë në liri dhe demokraci, Profesor Prifti ka shkruar se, “Kallajxhiu në radhë të parë ishte njeriu që tregonte vazhdimisht kujdes për kombin shqiptar. Në të njëtën kohë, ai kishte ndjenja të forta simpatie dhe admirimi për Amerikën. Nga kjo anë, ai i ngjante shumë Fan Nolit, i cili gjithë jetën ia kushtoi mbrojtjes së interesave të kombit shqiptar, duke punuar me përkushtim t’i sillte popullit shqiptar demokracinë wilsoniane”. Peter Prifti vlerëson lartë edhe spirtin demokratik të Xhevatit duke thënë se, “Kallajxhiu, po ashtu, ishte avokat i zjarrt i parimeve dhe idealeve demokratike. Përkrahja e tij ndaj parimeve demokratike të jetës daton qysh nga Gjirokastra, ku ai botoi gazetën me titull “Demokratia”. Demokracia, liria, pavarësia dhe paqeja këto nuk kanë qenë thjesht slogane për Kallajxhiun, por kushte vitale të domosdoshme për një shoqëri të drejtë e të mirëqeverisur”, përfundon vlerësimin e tij Profesor Peter Prifti.

Xhevat Kallajxhiu ishte njeri i mirë e i ndershëm, atdhetar i patundur — e donte Shqipërinë me gjithë zemër, por donte edhe Amerikën që i kishte dhënë strehimin, lirinë dhe mundësinë për të ushtruar gazetarinë dhe për të shprehur lirisht mendimet dhe pikëpamjet e tija, të cilat tani janë bërë pjesë jo vetëm e thesarit të çmueshëm të gazetarisë dhe të kulturës shqiptaro-amerikane, por edhe të shqiptarëve në përgjithësi. Një bashkohas dhe mik i Xhevatit, Nexhat Peshkëpia ishte shprehur se i “hidhur është mërgimi dhe të hidhura janë rrugët e tija”. Edhe për Xhevatin, si edhe për shumë bashkombas të tij, që u detyruan të largoheshin nga Atdheu i tyre, rrugët e mërgimit ku vdiq me mall për Atdheun, ishin vërtetë të hidhura, por megjithëkëte ai ishte gjithmonë optimist se do të vinte dita e lirisë, shpresë që ai e kishte shprehur me vjershën, “Do të vijë dita”:

Do të vijë më së fundi dit’ e madhe e çlirimit,

Do të shuhet skllavëria, do dërmohet trathëtija,

Do gjëmojë an’ e mbanë këng’ e ëmbël gëzimit,

Do të zhduket llahtarija, do t’ shpëtojë Shqipëria.

Dhe shqiponj’ e arratisur do të zërë vend’ e saj;

Do të ndizet sërish vatra, do të hiqet fut’ e zezë,

Do të marrë frymë biri, s’do të ketë lojë e vaj,

Do qindiset Shenj’ e Kombit veç me fjalë të lirisë.

Eh, zinxhir’ i tiranisë do të thyhet më në fund.

Mbaju, mbaju Mëma jonë, si që moti, gjith’ krenare

Edhe ti o bir i shqipes qëndro burrë mos u tund,

Se së shpejti do agojë dit’ e bukur shqipëtare!

——————————————————-

Me nderim, mirënjohje dhe me mall përkujtoj mësuesin dhe bashkpuntorin, njërin prej përfaqsuesve më të denjë të diasporës shqiptaro-amerikane dhe të intelektualizmit shiqptar në përgjithësi Xhevat Kallajxhiun me rastin e 25-vjetorit të ndarjes së tij nga kjo jetë.

FRANK SHKRELI

Natë historike dhe një premtim edhe më i madh për 2026-n, nga Albanian Roots: New York Yankees, ekipi më legjendar i bejsbollit amerikan, do t’i kushtojë një ndeshje të tërë komunitetit shqiptaro-amerikan!

Fotografitë nga Vasjana Minga

Festimi, në të ashtuquajturën zemra e botës “Times Square” New York City, u mbulua tërësisht nga ngjyra kuq e zi. Mbrëmjen e 22 nëntorit 2025, në kuadër të Muajit Shqiptar dhe 113-vjetorit të Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë, organizata Albanian Roots – Rrënjët Shqiptare me president z. Marko Kepi, Bujar Gjata, Bedrana Duka, dhe “Mjeshtren e Madhe” Agjelina Nika, organizuan paradën e makinave shqiptare në zemër të Manhattan-it duke e shoqëruar me një spektakël kulturor njëorësh pikërisht në Times Square.

Dhjetëra makina të stolisura me flamuj shqiptarë dhe amerikanë parakaluan nëpër Broadëay dhe Seventh Avenue, ndërsa në mes të sheshit legjendar u shpalos edhe një flamur gjigand kuq e zi.

Valltarë dhe këngëtarë të rinj të grupit “Albanian Roots Dancers” me veshje tradicionale, kërcenin me pjësëmarrësit vallen e Tropojës, Labërisë dhe Çamërisë nën dritat vezulluese neon. Turistë nga të katër anët e globit, njujorkez dhe vizitor të tjerë ndalonin të mahnitur, bënin foto dhe video, disa madje pyesnin: “I cilit vendi është ky flamur dhe kjo festë që ka kaq shpirt dhe kaq shumë bukuri?”

Për një orë të tërë Times Square në qendër të saj u mbush me flamujt kuq e zi dhe bë një “Shqipëri e Vogël” në zemër të Nju Jorkut. Flamujt kuq e zi valëviteshin krah për krah me Stars and Stripes si simbol i dashurisë së dyfishtë për vendlindjen dhe për Amerikën që na strehoi. Atmosfer festive, dhe britmat “Jam krenar me qenë Shqiptar!” dhe Albania! Albania! “USA! USA!”, u bashkuan në një kor të vetëm në Times Square.

Rrënjët Shqiptare: nata e flamurit kuq e zi në Times Square ( 22 nëntor2025) nuk ishte fundi, ishte vetëm fillimi.

Në kulmin e festës, mbrëm në një billboard z. Marko Kepi dhe drejtuesit e Albanian Roots z. Bujar Gjata dhe znj. Bedrana Duka, shpallën lajmin që do të hyjë në histori: New York Yankees, ekipi më legjendar i bejsbollit amerikan, do t’i kushtojë një ndeshje të tërë komunitetit shqiptaro-amerikan!

Ngjarja sipas tyre dotë jetë më 19 maj 2026, në Yankee Stadium dhe do të quhet Dita Zyrtare e Trashëgimisë Shqiptare, e cila mbahet për her të parë në një stadium amerikan ku një skuadër e Major League Baseball i dedikon edhe një ndeshje të plotë një komuniteti etnik si komuniteti shqiptar në Nju Jork.

Do të ketë rast thotë organizata Rrënjët Shqiptare që të zhvillohet edhe një paradë shqiptare brenda fushës legjendare, ku pjesëmarrësit do të mbajnë kapela dhe bulza me dy simbole “Yankees me flamurin kuq e zi ” (edicion i kufizuar falas), seksion të madh kuq e zi dhe përvojë VIP për të gjithë ata që blejnë biletat vetëm përmes linkut zyrtar të Albanian Roots (ëëë.albanianroots.com/yankees).

Rrënjët Shqiptare: “Është momenti të tregojmë botës se sa të mëdhenj jemi kur jemi të bashkuar.”

Nga Times Square te Yankee Stadium thotë Rrënjët Shqiptare rruga është e hapur dhe na pret. Tani është radha e juaj që të

bleni biletat, të veshni fanellat kuq e zi, të marrni fëmijët dhe këdo, të marshoni krenarë në fushën ku kanë luajtur leghendat amerikane të bejsbollit Babe Ruth dhe Derek Jeter.

Albania Roots – Rrënjët Shqiptare thotë: Le të mos jetë kjo vetëm një natë kujtimesh, por fillimi i një tradite të re ku çdo shqiptar në Amerikë ndihet më i fortë, më krenar dhe më i bashkuar se kurrë, edhe Yankee Stadium të bëhet një ditë kuq e zi para dhjetra mijërave tifozëve të skuadrës së tyre të zemrës Yankee./Illyria

Konferenca e Valbonës-Tropojë dhe synimet antikombëtare të organizatorëve të saj- Nga Agron Isa Gjedia

Konferenca e Valbonës-Tropojë dhe synimet antikombëtare të organizatorëve të saj- Nga Agron Isa Gjedia

KUR BIJTË E SAJ I VLERËSON KRAHINA- Përgatiti: Besnik Bedollari (Poet, publicist)

KUR BIJTË E SAJ I VLERËSON KRAHINA- Përgatiti: Besnik Bedollari (Poet, publicist)

Historia e panjohur e dy familjeve antikomuniste nga Puka: Çun Kuraj u arratis së bashku me të shoqen dhe vajzën e 7 muajshe, por shpejt u përhap lajmi i kobshëm se duke kaluar Drinin

Historia e panjohur e dy familjeve antikomuniste nga Puka: Çun Kuraj u arratis së bashku me të shoqen dhe vajzën e 7 muajshe, por shpejt u përhap lajmi i kobshëm se duke kaluar Drinin

KABALISTI I BROADWAY-T LINDOR- Tregim nga ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER (NOBEL, 1978)- Pёrktheu: Mimoza Erebara

KABALISTI I BROADWAY-T LINDOR- Tregim nga ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER (NOBEL, 1978)- Pёrktheu: Mimoza Erebara

“Miku im, ti nuk ke vdekur! Na ike herët dhe padrejtësisht”- Fjalimi prekës i Big Mamës për Shpat Kasapin: Kjo nuk është lamtumirë, por shihemi përsëri

“Miku im, ti nuk ke vdekur! Na ike herët dhe padrejtësisht”- Fjalimi prekës i Big Mamës për Shpat Kasapin: Kjo nuk është lamtumirë, por shihemi përsëri

GJURMËVE TË RRËNJËVE TONA – EDICIONI I TRETË: AKADEMI KULTURORE NË 400 -VJETORIN E LINDJES SË ERUDITIT SHQIPTAR IMZOT PJETËR BOGDANIT

GJURMËVE TË RRËNJËVE TONA – EDICIONI I TRETË: AKADEMI KULTURORE NË 400 -VJETORIN E LINDJES SË ERUDITIT SHQIPTAR IMZOT PJETËR BOGDANIT

Gjenevë, Partia Popullore (SVP) kërkon të shfuqizojë të drejtën e votës së të huajve

Gjenevë, Partia Popullore (SVP) kërkon të shfuqizojë të drejtën e votës së të huajve

Gazetari ukrainas ndalon “vajzën” e Putinit në Paris: Thuaji të ndalë luftën! Luiza Rozova: Më vjen shumë keq, nuk jam unë përgjegjëse për situatën (VIDEO)

Gazetari ukrainas ndalon “vajzën” e Putinit në Paris: Thuaji të ndalë luftën! Luiza Rozova: Më vjen shumë keq, nuk jam unë përgjegjëse për situatën (VIDEO)

Publikohet LISTA e vendeve më të sigurta në botë! Shqipëria pëson rënie, ja në cilin vend renditet

Publikohet LISTA e vendeve më të sigurta në botë! Shqipëria pëson rënie, ja në cilin vend renditet

Mediat izraelite: Trumpi ka gati fazën e dytë të planit të paqes në Gaza! Hamas drejt dorëzimit të armëve

Mediat izraelite: Trumpi ka gati fazën e dytë të planit të paqes në Gaza! Hamas drejt dorëzimit të armëve

Shqipëria parashikon ngritja e 20 qendrave të reja pritëse për emigrantë nga Afganistani, Pakistan, Irani, Siria, Libani dhe Gaza!

Shqipëria parashikon ngritja e 20 qendrave të reja pritëse për emigrantë nga Afganistani, Pakistan, Irani, Siria, Libani dhe Gaza!

Takimet e Enver Hoxhës me oficerët e Wehrmacht dhe marrëveshja e fshehtë e shtatorit ‘44! Rrëfimi i truprojës, zbardhen dokumentet

Takimet e Enver Hoxhës me oficerët e Wehrmacht dhe marrëveshja e fshehtë e shtatorit ‘44! Rrëfimi i truprojës, zbardhen dokumentet

Botues:

Elida Buçpapaj dhe Skënder Buçpapaj

Moto:

Mbroje të vërtetën - Defend the Truth

Copyright © 2022

Komentet