In September, the Geneva University Hospital (HUG) performed European first: a partial heart transplant on a 12-year-old patient with a complex congenital heart defect. This highly complex surgical technique replaces only the failing structures, transplanting just part of the donor heart, specifically the valves, while preserving the child’s own heart. The operation involved grafting the two valves responsible for pumping blood out of the heart, the aortic valve and the pulmonary valve. Unlike conventional valves, which are routinely used, the transplanted valves will grow with the child, avoiding repeated surgery and potentially offering a lifelong solution. The young patient is well and continues to recover under medical supervision.

Since the first operation of this kind in 2022, only around thirty partial heart transplants have been performed, all in the United States. This European first at HUG, was led by paediatric cardiac surgeon, Dr Tornike Sologashvili under the initiative of paediatric cardiologist, Dr Julie Wacker. This procedure opens important prospects for patients with selected congenital heart defects.

A revolutionary technique

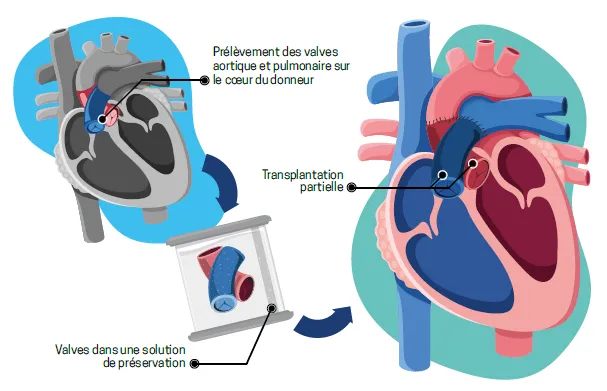

Unlike a full heart transplant, which involves replacing the entire heart, partial heart transplantation concerns only the valvular structures between the heart and the great vessels, specifically the aortic and pulmonary valves. These healthy valves are harvested from a donor whose whole heart cannot be used for full transplant, either due to impaired cardiac function or the absence of a compatible recipient.

The heart has four chambers and four valves, namely the tricuspid, pulmonary, mitral and aortic valves. These valves function like unidirectional gates, preventing blood from flowing backwards. When they malfunction, for example due to a malformation present at birth, the heart can no longer function properly. Whenever possible, surgeons favour valve repair over replacement. Some children are born without a valve or with valves so severely malformed that repair is not feasible. Valve replacement then becomes essential, using either a mechanical or a biological prosthesis. Mechanical valves require lifelong anticoagulation therapy, while biological valves deteriorate over time, necessitating repeated replacements, which is particularly problematic in a growing child.

A mother’s testimony

The young patient in question, suffering from a complex congenital defect called persistent truncus arteriosus (common arterial trunk), had already undergone three operations in another canton, receiving biological valve prostheses each time. After these operations, the child was able to live a nearly normal life. However, in recent years, both replaced valves began to fail, causing symptoms that limited physical activity. The aortic valve, in particular, developed a critical stenosis, a severe narrowing. “He compared himself to his friends: he wasn’t as fast as them or as strong as them, his mother recalls. He started giving up some hobbies because he was too tired. The hardest part for him was when his body just said no.”

The patient was then referred to HUG. The two traditional options available, replacing the valve once again with a biological prosthesis or implanting a mechanical valve, were far from ideal in view of this patient’s profile. They would have implied either a further operation within a few years or anticoagulation therapy that was contra-indicated due to comorbidities.

For this reason, the team considered a novel therapeutic approach. “We had to decide between worse and worse and… something new. We have a bright 12-year-old boy who knows his body and was excited about the possibility; it meant far less fear for him than facing a future where he couldn’t really live.”

A surgical feat offering numerous advantages

For the past two years, Dr Julie Wacker and Dr Tornike Sologashvili have been developing this partial heart transplantation programme. This technically demanding procedure represents a major medical advance. As Dr Julie Wacker explains: “The heart muscle is preserved, the risk of rejection is markedly reduced and the need for immunosuppressive therapy is limited. Moreover, the valves can grow with the child, potentially removing the need for repeated procedures as the child develops.”

“The success of this five-hour procedure hinges on exemplary collaboration across multiple medical disciplines,” notes Dr Tornike Sologashvili. “Cardiac surgeons, paediatric cardiologists, immunologists, anaesthetists and clinical care teams, particularly those in intensive care and paediatrics, together with transplant coordinators, pooled their expertise for this young patient, opening prospects for many others in the future.”

This European first was made possible through the support of the medical director of HUG, the clinical ethics board of the HUG, the Fondation Swisstransplant [Swisstransplant Foundation], and the Office fédéral de la santé publique (OFSP) [Federal Office of Public Health].

It confirms the national leadership of the paediatric cardiology and paediatric cardiac surgery units at the HUG in diagnosing and managing the most complex cardiac conditions in children and adolescents.

In numbers

The paediatric cardiology unit at the HUG manages all childhood heart diseases, from the prenatal period through to adulthood. Approximately 1 in 100 children is born with a congenital heart defect, and between 30% and 40% of them require an intervention, surgical or catheter-based. Between 220 and 250 paediatric cardiac surgeries are performed each year at the HUG. More than 60% of congenital heart defects referred to the HUG for cardiac surgery are considered complex or highly complex. Cardiac surgery is carried out according to the type of malformation. In some cases, it takes place immediately after birth; in others, it is scheduled weeks, months or even years later.

Care at the Hôpital des enfants [Children’s Hospital] is multidisciplinary, bringing together paediatric cardiac surgeons, paediatric cardiologists, anaesthetists, intensive care physicians and radiologists. A weekly case conference reviews each young patient’s situation, determining the best possible treatment strategies. Other specialists can be involved when needed.